The following essay was originally published in Auburn University AlumNews in May 1968. At the time of writing, the subject was a recent discovery for the author, and he quickly became deeply enamored with it. This piece offers an early glimpse into the perspectives of Buell E. Cobb, Jr., a scholar and writer who would go on to become one of the most influential voices in the study and preservation of Sacred Harp singing.

This essay captures a time that is now past — a time of transition, when fresh eyes were turning toward a tradition that had, after a revival decades before, waned once more into an obscure state. The Sacred Harp community had endured, as it always had, through the devotion of those who had never ceased singing. But outside interest was stirring once more, part of the natural ebb and flow that has marked the tradition’s history. The late 1960s were a period of quiet but significant change, when voices new to the hollow square began to swell its sound once again.

Cobb’s own journey was part of this shift. What had been, to him, an unfamiliar world of strange harmonies and anachronistic devotion quickly became a passion — one that would shape his scholarship, his friendships, and his life’s work. He was among those who found themselves drawn to a practice that seemed both timeless and startlingly alive, an encounter that would help set the stage for the great Sacred Harp revival of the late 20th century.

This moment of renewal was not the first, nor would it be the last. Sacred Harp has always been defined by cycles of scarcity and resurgence. The songs remain, waiting to be rediscovered, their voices rising again in each new generation. In this essay, we see Cobb at the threshold of that rediscovery—one singer among many whose presence would help ensure that this music, once thought to be fading, would instead find new strength.

Cobb is known among singers for his books Like Cords Around My Heart: A Sacred Harp Memoir (2013) and The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music (1978), both of which have shaped contemporary understanding of this enduring musical tradition. From 1969 to 1976, he taught English at West Georgia College (now the University of West Georgia). A longtime resident of Birmingham, Alabama, Cobb played a crucial role in the Sacred Harp community, serving as president of the Sacred Harp Publishing Company and chairing the National Sacred Harp Singing Convention for fifteen years.

Notably, this essay does not appear in John Bealle’s comprehensive bibliography of shape-note materials published in 1998 (available at fasola.org), which shows his extremely wide and deep study of the idiom, deftly compiled into his book Public Worship, Private Faith. However, Cobb’s contributions to Sacred Harp scholarship are well-documented, with several of his works included in Bealle’s bibliography. These include:

- 1968. The Sacred Harp of the South: A Study of Origins, Practices, and Present Implications. Louisiana Studies 7(Summer): 107–21.

- 1969. The Sacred Harp: An Overview of a Tradition. M.A. thesis, Auburn University.

- 1974. The Sacred Harp: Rhythm and Ritual in the Southland. Virginia Quarterly Review.

- 1977. Fasola Folk: Sacred Harp Singing in the South. Southern Exposure 5(2/3): 48–53.

- 1978. The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. Athens: University of Georgia Press.

- 1979. Liner notes to Word of Mouth Chorus, Rivers of Delight: American Folk Hymns from the Sacred Harp Tradition. New York: Nonesuch Records, H-71360.

- 1995. Sand Mountain’s Wootten Family: Sacred Harp Singers. In In the Spirit: Alabama’s Sacred Music Traditions, edited by Henry Willett, 40–49. Montgomery, Alabama: Black Belt Press.

The discovery of this previously unlisted essay provides an opportunity to reconsider Cobb’s early engagement with Sacred Harp and how it evolved into a lifelong passion. It stands as an insightful artifact from the formative period of a scholar whose work continues to influence singers and researchers alike. This article has been republished with the author’s awareness.

-Kevin Isaac

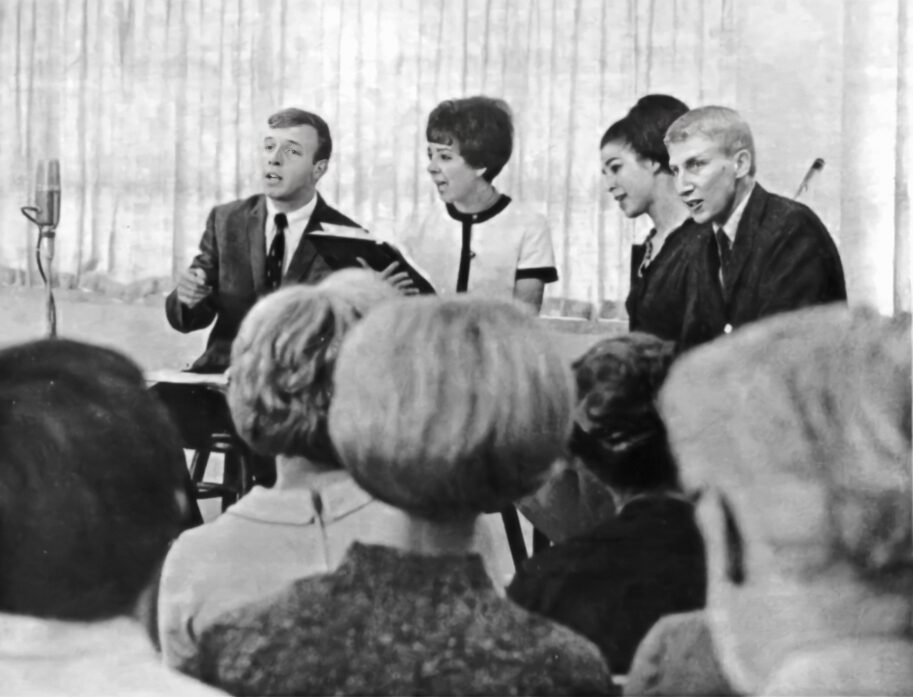

English Graduate Students Bring To Campus—

Sacred Harp—A Tradition Oblivious Of Modernity

By Buell Cobb

In our age of the folk singer and the hootenanny, a relatively unnoticed folk singing tradition called the Sacred Harp goes on deep in the rural South — a tradition oblivious to modern communications and influences. For several decades the Sacred Harp practices virtually have been unknown even in the South, except by rural villagers or city-dwellers only a generation or so removed from the country. The lack of communication is understandable. The Southern urbanite, of course, has not invited public attention to this curiosity in his back yard. Sacred Harp is not far enough removed for him to escape the distaste of association: for, as Donald Davidson wrote in respect to Southern Literature, “perhaps the Southern tradition has been made to look a little shabby in the brazen glitter of modern opinion.”

Nor have the fasola folk, as the Sacred Harp Singers have come to be known, tried to merchandise their art to the outside world; indeed, it would be out of place there. Doubtless there is little virtue in a system of solmization whose practical value became obsolete with the appearance of notated song books and organs in churches. What the Sacred Harp people could advocate instead would be the philosophy embodied in the Sacred Harp— provincialism, orientation in nature, a predilection for tradition, and religion.

Religious Folk Music

Even in the Bible Belt, the fasola singing, built around a venerable book of song, The Sacred Harp, is in a limited sense, a type of religious folk music in a secular world. The commercialized “gospel singing” whose participants have moved a little closer to town has almost drowned the Sacred Harp. The modern gospel musical with its jazz-oriented chord structure contrasts to the Sacred Harp constructed with modal patterns dating to Medieval times and fugal patterns that are vestiges of the 16th and 17th century polyphonic music of England. The wide philosophic gap between the two forms of religious song is evident in their conceptions of the Christian’s ascent to Heaven. Modern gospel music offers the analogy of a jet flight in the song, “My non-stop Flight to Glory.” The Sacred Harp view is more traditional and apparently more sincere: the soul “wings its way to heaven, mounts the skies, and with joy outstrips the wind.”

The early fasola folk tapped many sources in obtaining their body of tunes. The Sacred Harp is heir to a rich melodic inheritance; tunes in the collections are by and large old melodies of England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales—melodies which were transmitted by oral tradition to the new world and kept alive by successive generations. The tunes of many of the Sacred Harp Songs are secular ballads which have been spiritualized. The melody of “To Die No More,” for example is that of the song, “Three Ravens,” and a variation of “Barbara Allen” is used for the song, “Heavenly Dove.”

The vigorous quality of the fiddler’s tunes and other dance melodies appealed to the Sacred Harpers and other early singing groups, who gave them sacred texts and drew them into their own body of song. For example, the melody of “The Old-Fashioned Bible,” is based on the dance tune, “Fisher’s Hornpipe,” while the words are a parody of “The Old Oaken Bucket.”

The Sacred Harp’s rooting in the South comes through two movements—the singing school and camp meeting revival. The singing school movement came south and flourished, bringing with it a type of music which the Southerners were to make their own. A singing teacher would come to town, organize a class on subscription and teach at a local meeting house for a few weeks. Teaching tonal relationships and intervals of pitch to the musically inexperienced was not easy, so the singing-school teachers originated a system to give a characteristic shape to each note and show instantly whether a note should be sung fa, sol, la, or mi. The students sang a song through, part by part, using the syllables until the melody was thoroughly learned, and then they learned the words. At the end of the singing school, the class held a recital and demonstrated to the countryside what they had learned. In the early days the singing of the notes was discarded for the final singing; but in the South it became a matter of tradition and a vital part of the singing itself.

An Elizabethan Form

Except for the printed shape notes, an American innovation, the system of solmization used by the Sacred Harpers dates to Elizabethan England. (Shakespeare closed one of Edmund’s soliloquies in King Lear with the sequence: “fa, sol, la, mi.”) The fugal pattern with its variety and interest for each part suited the rural southerners so well that, while in other parts it became gradually unknown, Sacred Harp writers are still composing songs in this form today.

Though different in atmosphere and method, the camp meeting ran a parallel course with the singing school on its influence on the Sacred Harp. The camp meeting originated around 1800 in the Kentucky-Tennessee area and with it the revival spiritual. The revival meetings were generally held in or around a log cabin, taking the form of social gatherings, free from aspects of denominationalism. Revival leaders sought individual participation in the wave of group emotionalism. Thus, the revival song which evolved was a repetitive chorus with brief verse parts, usually the gleanings from familiar hymns by Isaac Watts or John Wesley.

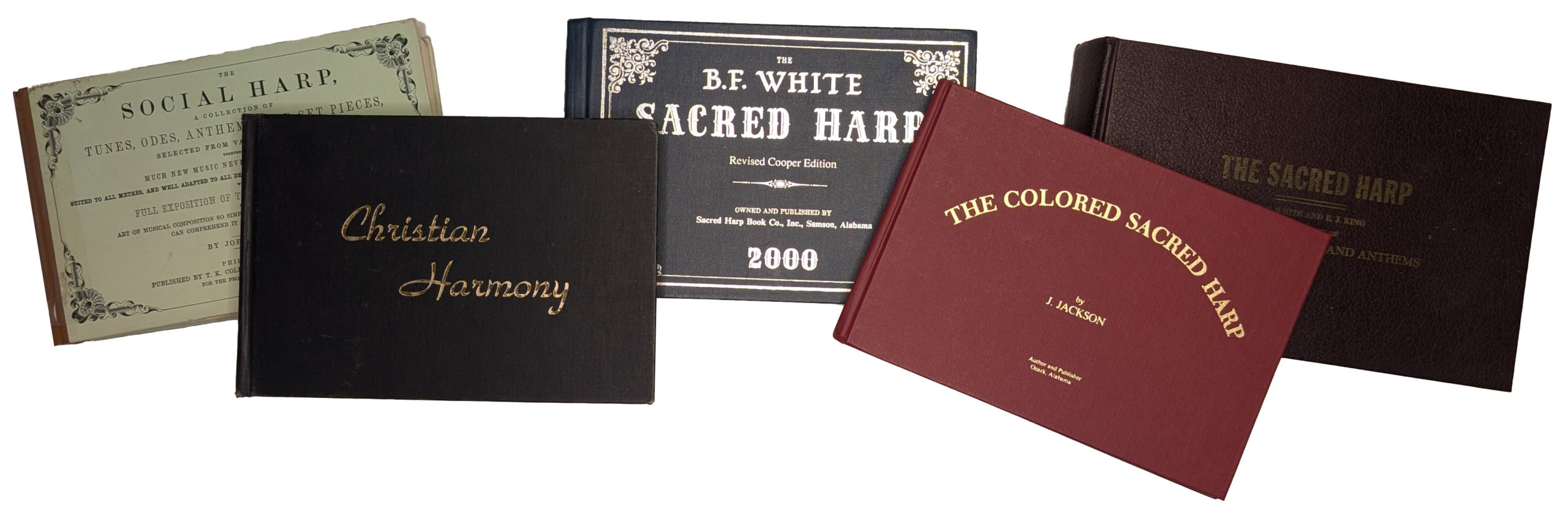

The successful camp-meeting spirituals attained a wide circulation and by the 1840’s many were being notated and included in song books. B. F. White, a Georgia singing school teacher, lawyer, and editor, drew many of the spirituals in to his 1944 song book The Sacred Harp. The Sacred Harp became the inspiration of a virtual cult of rural southerners and serves as the official song book today. Its most recent revision came in 1966, and includes a number of new songs, written in the same style as the originals.

Some of the foremost analysts of Southern culture have directed their considerations to the Sacred Harp or have brushed against it in discussions of religion, provincialism, and folkways in the South. Most important of these in relation to a study of the Sacred Harp itself are the Southern Agrarians, who interpret favorably the role of the Sacred Harp in its broad cultural contexts, seeing in it a number of the characteristics which together define the Agrarian ideal. If not for the Agrarians and one of their Vanderbilt associates, Dr. George Pullen Jackson, who has written six books and numerous articles about Sacred Harp, there would be little scholarly recognition of the Sacred Harp today.

To the Agrarians the Sacred Harp is one of the last fortresses of the traditional way of life. Many of the old ways are evident in the tradition of the Sacred Harp which Dr. Jackson describes: All singings are opened and closed with prayer. The traditional dinner-on-the-grounds is always ‘graced,’ likewise. When one singer calls another one ‘brother’ or ‘sister,’ and the older ones ‘uncle’ and ‘aunt,’ it has a real and deep significance. It means that Sacred Harp singers feel themselves as belonging to one great family or clan. This feeling is without doubt deepened by the consciousness that they stand alone in their undertaking—keeping the old songs resounding in a world which has gone over to lighter, more ‘entertaining,’ and frivolous types of song or has given up all community singing.In 1930 Andrew Lytle wrote, in regard to modernism and the Southern way of life: “…the country church languishes, the square dance disappears … but the Sacred Harp gatherings and to a lesser extent, the political picnics and barbecues, have so far withstood the onslaught..” Modernization has doubtless made considerable inroad into the Sacred Harp territories since that time. But the fasola singers are proud that their singings are numerous and well-attended. (The most recent Directory and Minutes of Annual Sacred Harp Singings records some 300 one-day singings attended by thousands of singers in Alabama and scattered parts of Florida, Georgia, Tennessee, and Mississippi in 1966.) However, there is a distressing awareness that the “old ways” hold less and less interest for the young people. The end is not yet in sight, because Sacred Harp is a vigorous tradition and its devotees intent upon its preservation. But the falterings are evident, and the knowledge of this gives each assembling of Sacred Harp singers a special poignancy for participants and sympathetic observers.

Leave a Reply