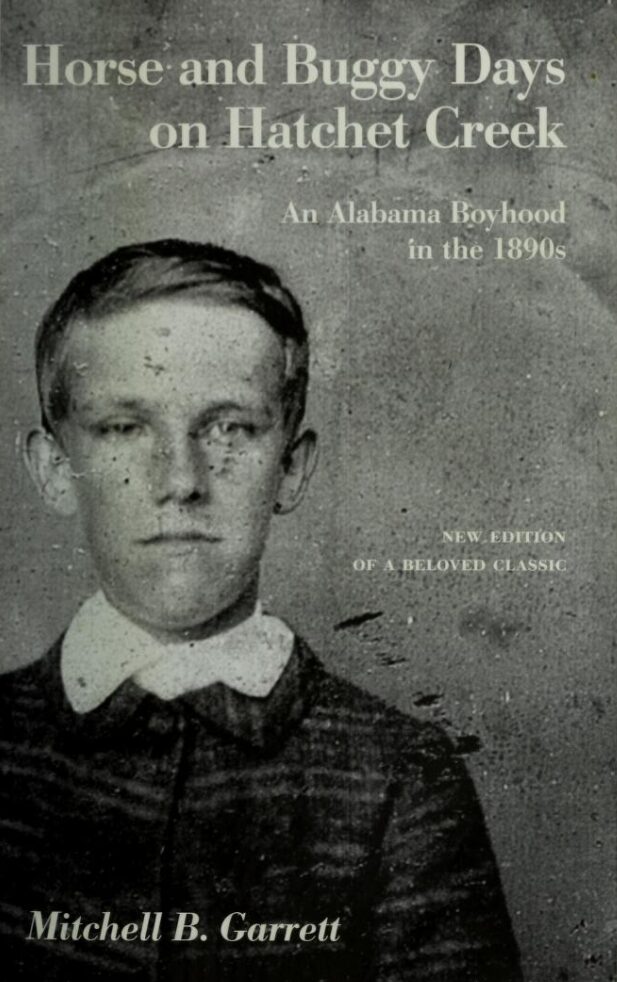

In the late 19th century, rural communities across the South and Midwest found joy and connection through the vibrant tradition of shape-note singing. Mitchell B. Garrett’s Horse and Buggy Days on Hatchet Creek: An Alabama Boyhood in the 1890s (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press) offers a rich firsthand account of how this musical practice flourished in the Hatchet Creek community, where Sacred Harp singers and seven-shape-note enthusiasts each cultivated their own distinct traditions.

For Sacred Harp singers, the focus was on participation rather than performance, with songs passed down by family connections and reinforced through lively singing schools. In contrast, the seven-shape-note tradition embraced more formal instruction and newer compositions, often led by teachers with professional training. Despite their differences, both styles brought people together for all-day singings, where melodies rang out from packed churches and open-air gatherings.

Garrett’s vivid description, in the chapter titled “Community Activities”, of these singings reminds us that shape-note music was more than just a pastime—it was a pillar of community life, a source of spiritual and social connection, and a tradition that continues to resonate with singers today.

COMMUNITY ACTIVITIES

MOST OF THE TIME, life in the Hatchet Creek community sixty-five years ago was monotonous. Anything that tended to break the monotony was seized upon and exploited. Eyes lighted up with pleasure when a neighbor was observed passing by. You hailed him from your front porch and “passed compliments” with him; that is to say, you engaged him in something like the following dialogue:

“How’re y’all?”

“Only toler’ble. The old woman grunts a right smart — pains in her jints.”

Whereupon you allowed as how you were not feelin’ very well yourself.

If the passer-by was in the mood to draw rein and tarry for further talk, you went out to the front gate and, leaning on the palings, carried on the conversation until a variety of topics had been covered.

On the Sundays when religious services were held in the churches, nearly everybody in the community put on bib and tucker and turned out, not only to listen to the sermon and the singing, but also to enjoy the society of friends and neighbors. Invitations to dinner were given and accepted, and a good time was had by all.

On many a Sunday afternoon, particularly in the summertime, people of the community gathered at one of the churches for a very zestful activity called a “singing.” After crops were laid by, one Sunday at least during the summer was devoted to an all-day singing, with free dinner on the ground, to which people from miles around were attracted.

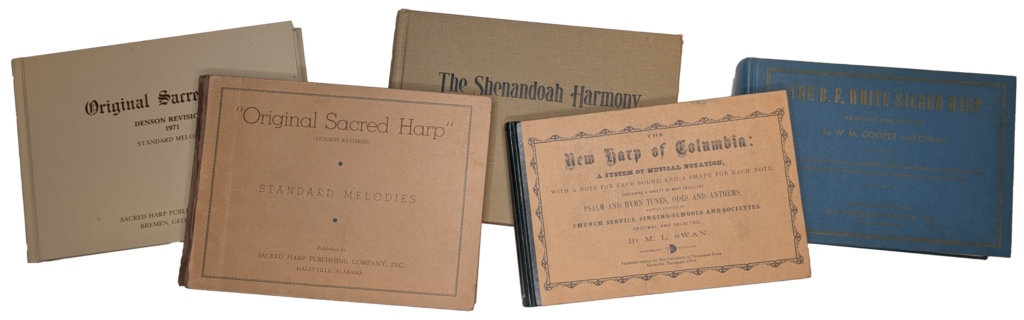

The music of these songfests was of two distinct brands, that of the Sacred Harp and that of the “seven shape notes.” The twain were never mixed.

The Sacred Harp still has a dwindling number of devotees in the South, but I shall speak of it in the past tense because it was revised in 1911 and ceased to be exactly the songbook that I knew in my youth.

The songs which it contained were, for the most part, melodies of England, Scotland, Ireland, and Wales, brought to our shores in the tenacious memories of our forefathers during colonial times and collected and published in the first edition of the Sacred Harp in 1844. Though the songs were religious, or at least tinged with religious sentiment, they were fundamentally folk songs and therefore not well fitted for incorporation in a church hymnal. Nevertheless, Primitive Baptists, though they never used the Sacred Harp in their church services, always placed the big oblong book of song next to the inspired Bible as the source of religious comfort and joy.

The music of the Sacred Harp was written in four notes: fa, sol, la, and mi, each with its individual shape. Fa was triangular, sol oval, la square, and mi diamond-shaped. Always before singing the words of a song, Sacred Harpers sang the notes, to make certain that the melody could be sung correctly before the sacred text was sung.

When engaged in singing, Sacred Harpers sat on benches forming three sides of a square. The leader stood in the middle. On the leader’s right sat the basses, in front of him the tenors, on his left the trebles (pronounced “tribbles”). Tenor was sung by both men and women, treble usually by women only. A sizeable “class” might consist of a dozen basses, two dozen tenors, and half a dozen trebles.

In contrast with common usage in choral music, there was in the music of the Sacred Harp no definite tune-carrying part. The tenor in a measure performed this service, but the bass and the treble indulged in about as much running around and up and down as the tenor did. An urbanite of the present day, with his standardized musical background, would not be favorably impressed by this brand of music. He would be irked by the shrill voices of some of the singers, by the staccato or trotting movement of the songs, by the discords, by the dearth of melody or tune, and by the fact that all the songs sound pretty much alike.

Here we uncover the secret of the Sacred Harp’s popularity: the songs were to be enjoyed by the singers, not necessarily by the audience.

Most of the songs were familiar to everybody and could therefore be sung by heart. When the leader, standing before the class, raised his arm and gave the down beat as the signal for the singing to begin, the response was a loud burst of sound. Drawing in deep breaths, the singers let out staccato yells. The arm of the leader, exact as a metronome, beat time; and the enthusiastic songsters, at full cry, kept on the beat. I have seen the Primitive Baptist Church in the Hatchet Creek community crowded on such occasions, people standing in the doorways, along the walls inside and around the open windows outside, all singing lustily. The basses rumbled, the tenors brayed at a high nasal pitch, and above all rose the screaming trebles. Beads of perspiration rolled down cheeks, but facial expressions were ecstatic.

Sacred Harpers normally learned to sing the songs of their beloved book from other Sacred Harpers and by constant practice, without the botheration of much formal instruction; but for teenage beginners, who needed encouragement and a little elementary knowledge of music, a ten day singing school was held at Shiloh Church nearly every summer after crops were laid by. The teacher of such a school was always a farmer, with limited education, who had acquired a considerable reputation in the community as a singer. To make up his school, he drafted a brief contract in which he specified the opening day, the length of the term, and the rate of tuition, and canvassed the community to determine the number of pupils that he was likely to have. If the number was sufficient to warrant the undertaking, the tidings were publicized and the school opened on the day specified.

On the morning of the opening day the teacher was met by twenty-five or thirty tuition paying pupils, who arrived on foot, in buggies, and possibly on horseback, bringing their lunches and song books with them. By nine o’clock the school was in session. After singing two or three familiar songs by way of creating the proper atmosphere, the teacher devoted an hour or more to formal instruction. On the blackboard he drew the four notes — fa, sol, la, mi — and drilled his pupils in running the scale. He showed them how to differentiate long notes from short notes; he showed them the marks that indicated “rest” and “repeat”; and he bade them look on their books and verify his instruction from observation. Then followed a recess for relaxation, after which the class divided tentatively into basses, tenors, and trebles. Songs were now sung, and occasional interruptions were made by the teacher to give further instruction.

In the afternoon the complexion of the class was changed considerably by the arrival of several experienced Sacred Harpers who came to participate in and enjoy the singing. These took seats among the tuition-paying pupils. The teacher was glad to welcome the visitors because they improved the quality of the singing and set examples for the novices to follow. So enthusiastic did the class now become that the singing continued with few interruptions until five.

Pretty much the same routine was followed on other days. The formal musical instruction never got beyond the most elementary stage, but the pupils learned to sing scores of songs, many of which were accounted difficult.

Although the teacher had little knowledge of music, he was expected to display two important accomplishments, namely, the ability to beat time vigorously with long sweeps of his right hand and arm, up and down, right and left, and the ability to sing any part in the song. Whenever the bass, tenor or treble lagged behind or broke down in performance he would rush to the support of the wavering or broken line and bring up the straggling forces. When any one of the parts got ahead of the others in performance, he would rush at the group that was singing too fast and burst into the unruly part of the song at the full power of his stentorian voice and swing his long right arm more vigorously than ever, to check the break-neck speed of the refractory warblers. By thus galloping around the sides of the square, he was able to keep all parts going and rarely failed to bring all in on the home stretch within a few measures of the same time.

On the last day of school the pupils, sitting on the front benches, and supported by many experienced singers on the back benches, gave an exhibition which lasted all day. After the school disbanded, the class continued to meet once a month on a Sunday afternoon, weather permitting, to keep in practice and possibly to improve their performance. The next summer there would probably be another “fa-so-la” singing school at Shiloh Church.

Devotees of the seven shape notes also had their singings on Sunday afternoons at either the Methodist or the Missionary Baptist Church, and likewise their singing schools in the summertime. But there was a difference in both the substance and the spirit of the performance. The seven noters had no sentimental attachment to any particular book. Indeed, they made it a practice to change books every year or so and thus keep up with the latest songs. Moreover, they could boast a little higher level of musical knowledge than the Sacred Harpers possessed.

The seven notes in question were do, re, mi, fa, so, la, ti, each with its individual shape. After a little practice in running the scale, a singer, given the pitch of a note to start with, could determine instantly the pitch of any other note in the scale by its shape. This simple device obviated the necessity of learning all that folderol about a, b, c, d, e, f, and g, which is such a stumbling block to beginners in their efforts to sing with nothing to guide them except round notes.

The music of the seven-shape-note variety was in four parts: bass, tenor, alto, and soprano. Soprano, which was definitely the tune-carrying part, was commonly sung by female voices.

Unlike the Sacred Harpers, the seven noters chose as the teacher of their singing school, if possible, a man who had studied vocal music under the direction of some famous teacher at some far-off place, like A. J. Showalter of Atlanta, Georgia, and who could display, printed in the new book which he proposed to introduce, a few melodies of his own composition. Such a man usually wore a necktie and was too distinguished to be called plain Mister; he was called Professor and treated with respect.

On the opening day of school the professor distributed copies of the new book among his pupils and stood ready to hand copies to all other interested persons. The price per copy ranged anywhere between fifty cents and one dollar. How much profit accrued to the professor from this transaction was of course never revealed.

Upon examination the new book would be found to bear some such title as Prayer and Praise, Gospel Songs, Make Christ King, Worship of God, Christ is Lord, or some other catchy word combination indicative of the contents. Many of the songs were standard gospel hymns; but many were of recent origin, and some were entirely new. The tendency was to include songs of a light, joyous nature, which would be appropriate for Sunday school. Sacred Harpers frequently scoffed at such songs on the ground that they lacked substance and were sung moreover to sacrilegious “jig” tunes.

The school normally lasted ten days. During this brief period the professor usually managed to impart to his pupils a fair amount of elementary musical knowledge. He taught them to run the scale; he called attention to flats and sharps; he drilled them in singing semi-tones; he even explained the purpose and value of clefs. At the close of the school there was the customary all-day exhibition, with free dinner on the ground for everybody, which was well attended and enjoyed by throngs of visitors. The scores of new songs which the pupils of the school, and other songsters as well, had learned to sing were thenceforth sung on Sunday mornings by Methodists and Missionary Baptists in their Sunday schools, at Sunday afternoon singings, at social gatherings of young people, and on other occasions. After a while, however, perhaps at the end of a year, the new songs began to grow stale and uninteresting, and the sentiment began to prevail that another singing school and a new song book were needed.

At singings and singing schools young people in particular had, or imagined they had, a great deal of fun; but the occasion par excellence for a good time by all, whether old or young, was the community picnic which took place nearly every summer. In the Clay County Advocate, under date of July 31, 1891, we have the following account by an eye witness of a picnic at Ingram’s mill:

By 10 o’clock in the morning a good audience had gathered, and at eleven Mr. A. S. Horn,¹ a student from the State University, made a welcome address, followed by an address by ye scribe, after which Prof. H. C. Simmons² made an interesting talk. Dinner was announced, and of course all partook of the nice delicacies prepared for the occasion. The afternoon was spent pleasantly with the young people. Some took buggy rides, some seated themselves beneath the green willow trees beside the pond and, as the merry chirp of the little birds echoed among the gentle zephyrs of the trees, and as the beautiful streamlet rippled over the pebbles, seeming to say, “Welcome, friends, one and all,” they told their sweet story of love, and ere the golden sun had bent low in the western skies, many a heart was made to rejoice and to exclaim that another pleasant day was numbered with the past.

Omitted from this lyrical account of young love in bloom, be it noted, was any reference to the presence of redbugs in the grass and ticks under those green willow trees.

Leave a Reply